There is an easy way to get regular exercise; and it can be done in no time at all!

15 minutes (But you’ll get hours back when you’ve read it)

Most of us want to get fitter. We start to put on weight, find ourselves breathless climbing the stairs or running for the bus (or don’t try either any more). We remember how much better we felt when we did regular exercise. It’s an odd thing: most of us know that exercise would make us healthier, that it helps keep our minds active, that it improves our mood and adds to our life expectancy, and yet we can’t find the time.

In fact, lack of time is the most commonly quoted reason for not exercising regularly, in a list that includes (ironically) not being fit enough, the cost of a gym membership, a dislike of gyms, family commitments (time again), not enjoying running and not liking to go out in inclement weather. Wouldn’t it be good if we could get our daily exercise, starting right now, without buying any new kit or even using up any of our valuable time?

Fortunately, there is one activity that will let us exercise regularly and avoids most of our pet hates. It doesn’t involve any of the costs, commitment to others and required levels of fitness to start, and it can make an enormous difference to our physical health, well-being and mental health (mood, stress levels and sense of well-being). This magic elixir is simply fitting in a short walk as part of your day. And, best of all, you can fit in regular walks without using up your precious time- a technique I call “time bargains”. Time bargains allows you to get your recommended 30 minutes exercise a day without spending 30 minutes doing it! This astonishing feat is achieved by building a walk into your everyday activities.

In 2005, I was hired as Head of Promoting Walking, for Britain’s walking charity the Ramblers. Two million people in the UK go on a country walk at least once a month, and the Ramblers work to keep the countryside open and welcoming to walkers. But 36 million people in the UK don’t do the Department of Health recommended minimum of 30 minutes exercise a day, and until my team was formed, there was no organised programme at the Ramblers to encourage people to get their exercise with a daily walk. I started a program called Get Walking, Keep Walking which got thousands of people walking independently for transport, recreation and health.

We found that most people don’t know that walking is the perfect exercise: it is easy to do, you can start from your doorstep, it’s free and it makes you fitter. In fact spending time walking adds to your life expectancy. But, many people just ‘don’t have the time’ to walk more. Well, I can help you find time to walk with the magic of Time Bargains.

How I discovered Time Bargains.

I had a meeting away from the office, and realised that it would be an enjoyable walk, and take about 50 minutes. I looked up the journey on a trip planner and found that it would take 47 minutes by bus, as there was no direct route. I couldn’t be late for the meeting so, given the unreliability of buses in traffic, I would have to allow an hour to be sure that I arrived on time. So, I set out on a brisk, sunny day and walked to my meeting in 52 minutes, including stopping to check my map, and back in 45 minutes as I now knew the route. I had several more meetings at the same place, and so each time I enjoyed 2 x 45 minute exercise sessions at no cost in time to either me or my employer! (In fact I saved time as I would have had to spend more time using public transport).

It occurred to me that there must be other journeys where this would be possible, and so I experimented with a number of enjoyable ways of including a walk into my regular journeys and Time Bargains were born!

It takes me about an hour to stroll through several parks to my favourite supermarket, Lidl, or about 40 minutes on two buses. So for 20 minutes extra I get an hours exercise, thus getting 40 minutes of free exercise! So this is how Time Bargains work; you get the exercise you want, and by fitting it into a journey you are making anyway, you get it in less time.

If you have a journey that takes say 45 minutes on a bus or train, you see if you can replace all or part of the journey by walking. You calculate how much longer it takes, and how much walking you get to do. You are not looking for the quickest way to get somewhere, you are looking for a built in opportunity to walk. For example if a journey takes half an hour longer by walking for an hour, you’ve got an hours exercise (the optimum daily dose) but only spent half an hour to get it. So, 30 minutes of your exercise cost you no time at all.

Anne takes a train each morning, and then a bus the last mile and a half to work. She waits an average of five minutes for the bus, which in London’s rush hour traffic takes about twenty minutes, then she walks five minutes to work. That’s 30 minutes for a mile and a half. One day after work Anne walked back to the station with a colleague, and found that it only took them thirty-five minutes. So, she discovered that for five minutes extra she could fit in thirty minutes more exercise than she was getting before. Anne soon found that as she continued walking back to the station in the evening, she cut the journey time down to 22 minutes. By giving herself 25 minutes, in case of a few lights against her, she could always catch the train she wanted, the 5.55, whereas when she took the bus, she often missed it by a minute or two. So, Anne gets a more pleasant, stress free, journey home, AND some brisk exercise, for less than no time at all! And, if that’s not a bargain I don’t know what is.

Another example is Vereena. She doesn’t have a way of using her journey to work to save time for walking, so she looked an alternative. She used to eat at her desk, and work through, and found that she often had a mid-afternoon slump around 3-4 pm. Now she goes for a brisk 30-40 minute lunchtime walk 3-4 days a week and on nice days stops and eats her sandwiches in a park. Sometimes, she invites a colleague, and they sort out a work problem as they walk. She finds that she usually can relax and get perspective on her work as she walks, usually not by thinking about it, but merely relaxing, and often she spends the last five minutes of the walk planning how to best spend the afternoon at work. She has found that her productivity has gone up, she less often needs to stay late to finish up her work, and her supervisor has commented on her cheerful and effective working habits.

This exercise is in her lunch hour, which she usually worked through. So, she gets fitter, and works better, at no cost to her schedule.

The principal is to look for ways of fitting at least 30 minutes of activity, usually walking, into your everyday activities. These examples involve building a walk into our daily commute, or other regular trip. It might take a bit of experimenting, but most of us have trips that can be modified to include a walk, and what’s better, can give us a useful period of exercise that costs fewer minutes than doing it as a stand-alone.

The great advantage of walking is that it can be fitted into almost every day. Especially, when you realise that 3 x 10 minutes is just as good as 30 minutes straight. I can often get in 5 or more minutes walking up and down the platform when waiting for a train (in otherwise wasted time), or check on the next bus due, and use any waiting time to walk one or two stops. Another advantage of walking is that on regular journeys, you can soon accurately predict the time the journey will take, and don’t need to build in extra time in case the bus is late, or you have difficulty finding parking etc.

Another way to get exercise without using any time is cycling. I can cycle to my friend Bob’s house in 20 minutes, but it takes 40 minutes on the bus. So I get 20 minutes exercise, and save 20 minutes too! I also climb escalators instead of standing, and usually take the stairs instead of the lift: both excellent exercise and neither costing any more time. Interestingly, an hours’ exercise adds more than an hour to your life expectancy. So time spent exercising is a very efficient use of time, both in the short term, and the long term.

When to walk

Any time is good! The advantage of a morning walk is that, if you have to postpone it, due to extreme weather, you still have plenty of time to get your thirty minutes in later in the day. Getting in exercise on the way to work is easy to plan, and it involves a consistent journey for most of us. There is also evidence that people who do exercise before work are wider awake and more productive. However, if you have a flexible approach to exercise, you may like to mix adding a walk to the morning commute with occasional lunch time walks and building a walk into the journey home or after work. The key is to exercise regularly and frequently; if possible, every day for a minimum of 30 minutes.

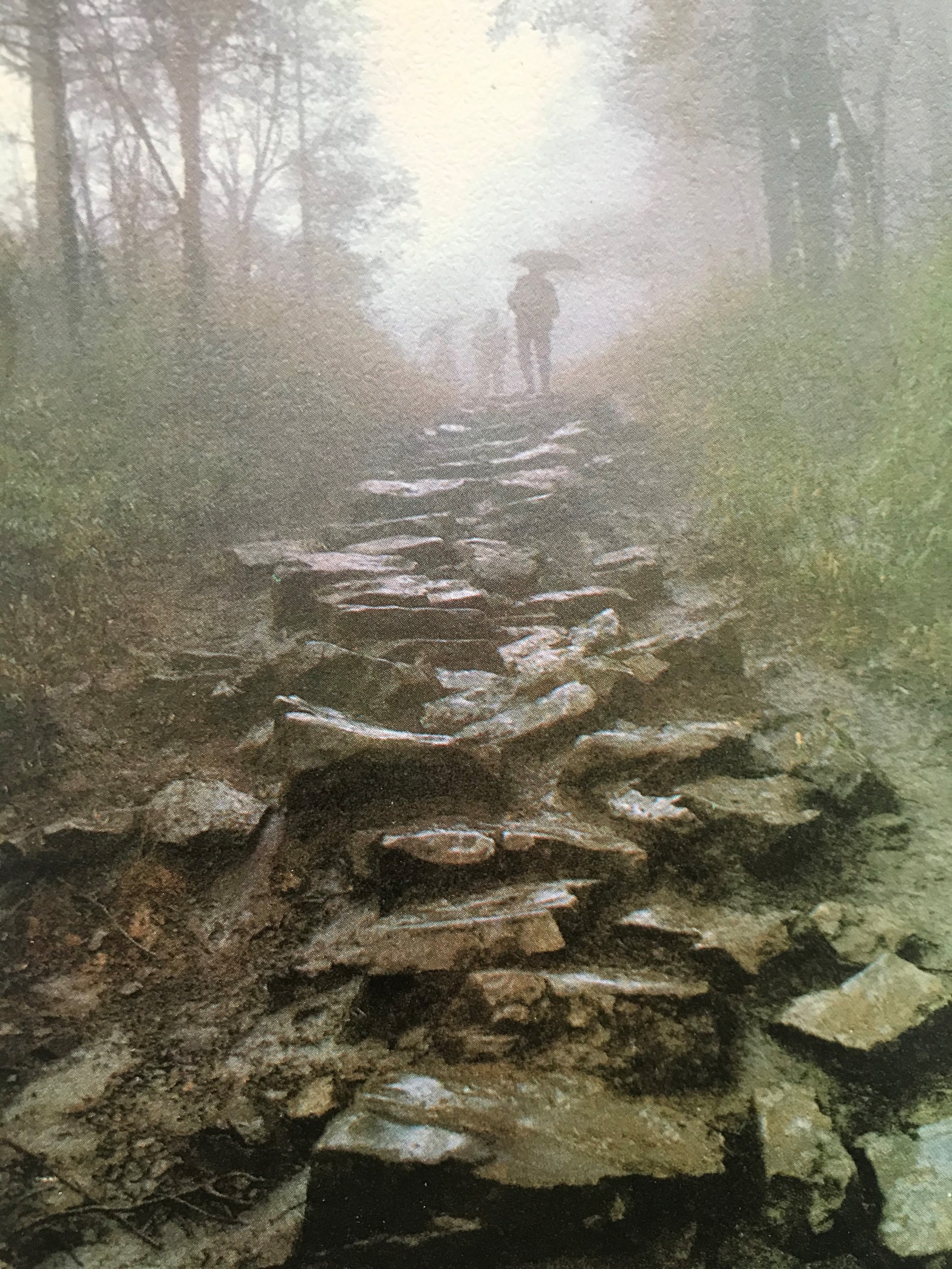

Dealing with the weather

You don’t want to get to work wet. However, you’ll find that it rains on your walk to work less often than you expect. But, if you commute at a fixed time, you will occasionally be faced with rain. Carrying a lightweight raincoat and/or an umbrella should keep you dry on all but the wettest and windiest days. Some people chose to carry a change of socks, or even walk in comfortable shoes and then change into their work shoes when they arrive.

When you realise how much better you feel from walking more you may add other enjoyable walks to your day, and appreciate life much more. As my physio told me at 70, when I said I wanted to get fit again after an accident: “You are never too old to get fitter!”

Most of us know we should do more exercise. But most people just can’t find the time. So, now you can exercise, get fit, and save time as well!

END

A few links to supportive evidence

Participants who walked 1 h or more per day have a longer life expectancy from 40 years of age than participants who walked less than 1 h per day.

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/1/2/bmjopen-2011-000240

Many other studies have found that walking helps lower blood pressure, keep weight down and improve mood. Substantial amounts of strolling have also been linked to slower memory decline and reduced risk of some cancers.

Walking your kids to school improves their life chances and academic success

https://www.utoronto.ca/news/why-walking-school-better-driving-your-kids

https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/1/2/bmjopen-2011-000240#

Walking improves life expectancy, and reduces health costs (as you are less often sick as well!)